Perched halfway between the old and the new, in the strange limbo of this processing station, they have not yet set foot on the continent that will change them, swallow their children, absorb all they know.

An older sister stands by the bag that holds the family’s clothes. The mother’s arm cradles the youngest. The world they left is miles and weeks behind.

We are privileged to glimpse them in the brief moment before transformation begins.

Could I leave family and birthplace, career and friends, -- all the known --to stake everything on a new land?

Tracing what I see, exploring the shapes of their expressions, their body language, I’m seeking to draw their courage into myself.

Each new stage of life is a risk that requires us to leave the known behind. Each time we go after a dream, we risk failure, put everything on the line, become more ourselves even as we enter alien territory.

Each necessary risk requires us to be more daring and more free.

The freedom that the United States offered nineteenth and early twentieth century immigrants was a clarion call. It said you have the chance to make a new life. To give your children what they otherwise could not have.

Like immigrants today, they arrived to find no guarantees. They risked being turned away at Ellis Island. They risked being unable to make a living in the new land. They risked having their children turn against them and reject the language and culture and even religion they had brought with them.

It seems to me that ageing is not unlike being an immigrant. Your language, your gestures belong to another place, another time. You don’t fit in. The place you worked so hard to make for yourself is irrelevant now – you have to make yourself under new conditions, sometimes hostile. People can resent you.

Is this part of why these faces haunt me?

The wide land they came to was beautiful and terrible. The cities were crowded, working conditions often cruel. Yet they persisted. They wanted more than anything to have the chance to live as free people. I don’t have photographs of my ancestors who came to the United States to find freedom to practice their religion or to make a new start. I can’t study their faces, so I study these, and find in them the way it looks to love freedom. And to bring with you in your clothes, your stance, how you hold your child and do your hair, a forgotten/sacrificed world.

What do we carry of our forebears?

Of the world they brought with them?

What risks do we take?

In these faces vanished worlds for a moment come alive.

Catherine Bancroft

Ellis Island opened in 1892. By the time it closed for good in 1954 it had seen more than 12 million people pass through its doors. The greatest number came during the early years of the 20th century -- a flood that slowed with the coming of the 1st World War, and later the anti-immigration legislation of 1924.

The book found in the Bala Library vestibule was Wilton Tifft and Thomas Dunne, Ellis Island (NY: WW Norton & Co Inc, 1971). The photographs that inspired these paintings come from the National Archives, the Library of Congress, the Department of Immigration and Naturalization, and the National Park Service.

Key to Paintings

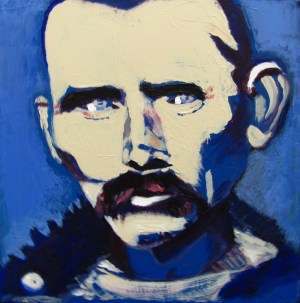

| White Bearded Man (sold) 12x12 |

|

|

|

Woman from Lapland (sold) 12x12 |

|

|

|

Romanian Man with Fur Collar (sold) 12x12 |

|

|

| |

| Man in Hat (sold)12x12 |

|

|

|

Emma Goldman (sold) 12x12 |

|

|

|

Romanian Man in Fur Hat 12x12 |

|

|

| |

| Woman from Guadaloupe (sold) 12x12 |

|

|

|

Child (sold) 12x12 |

|

|

|

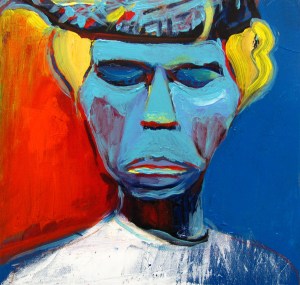

Black Bearded Man 12x12 |

|

|

| |

| Magyar Woman (sold) 12x12 |

|

|

|

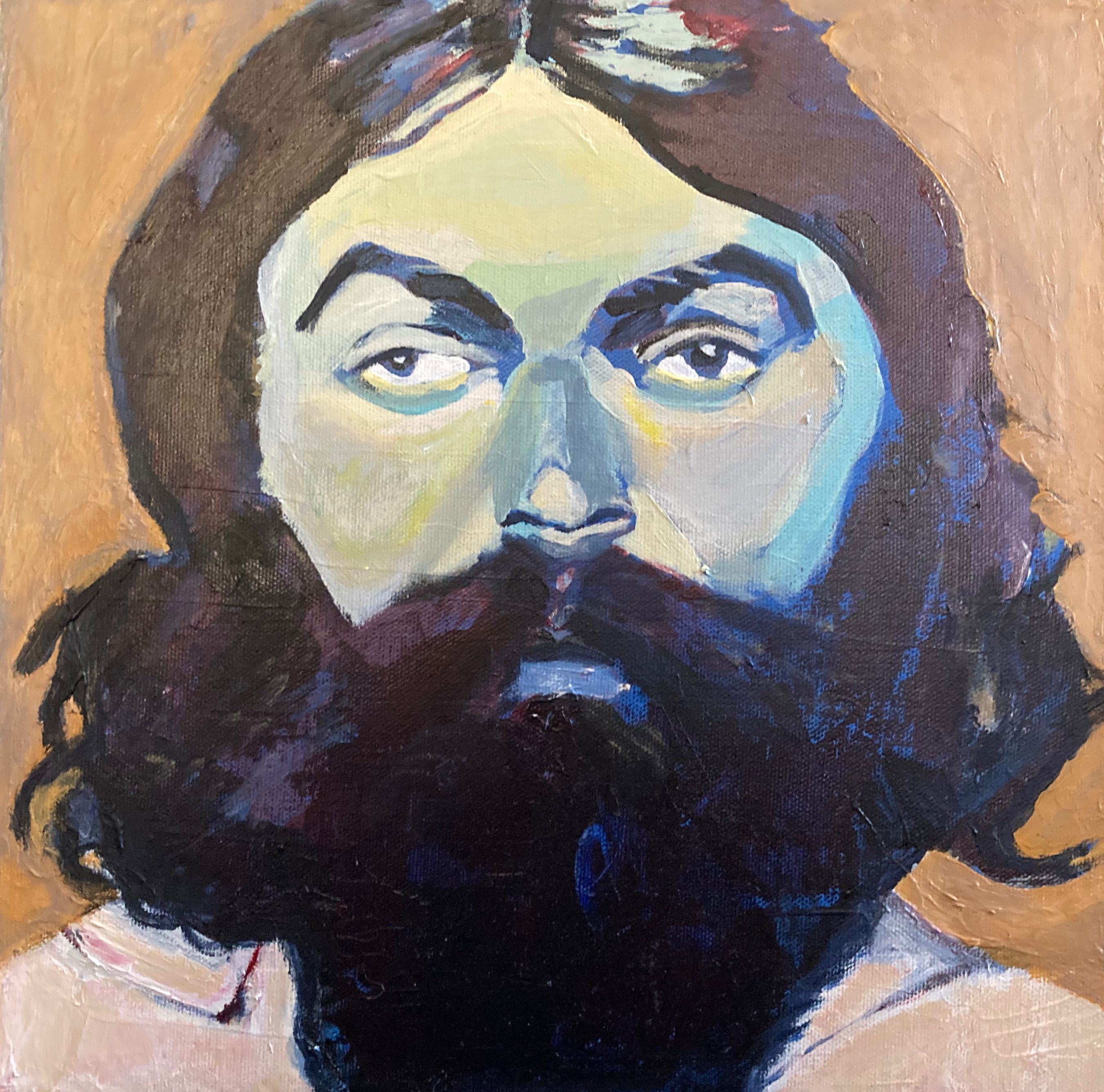

Man from Scotland (sold) 12x12 |

|

|

|

Woman from Ruthenia (sold) 12x12 |

|

|

| |

| Just Arrived (sold) 16x20 |

|

|

|

Examination Room 10x20 |

|

|

|

Family Group in Kerchiefs (sold) 10x20 |

|

|

| |

| Couple (sold) 20x20 |

|

|

|

Irish Immigrants (sold) 20x24 |

|

|

|

Two Sisters 20x20 |

|

|

| |

| Waiting Room (sold) 10x10 |

|

|

|

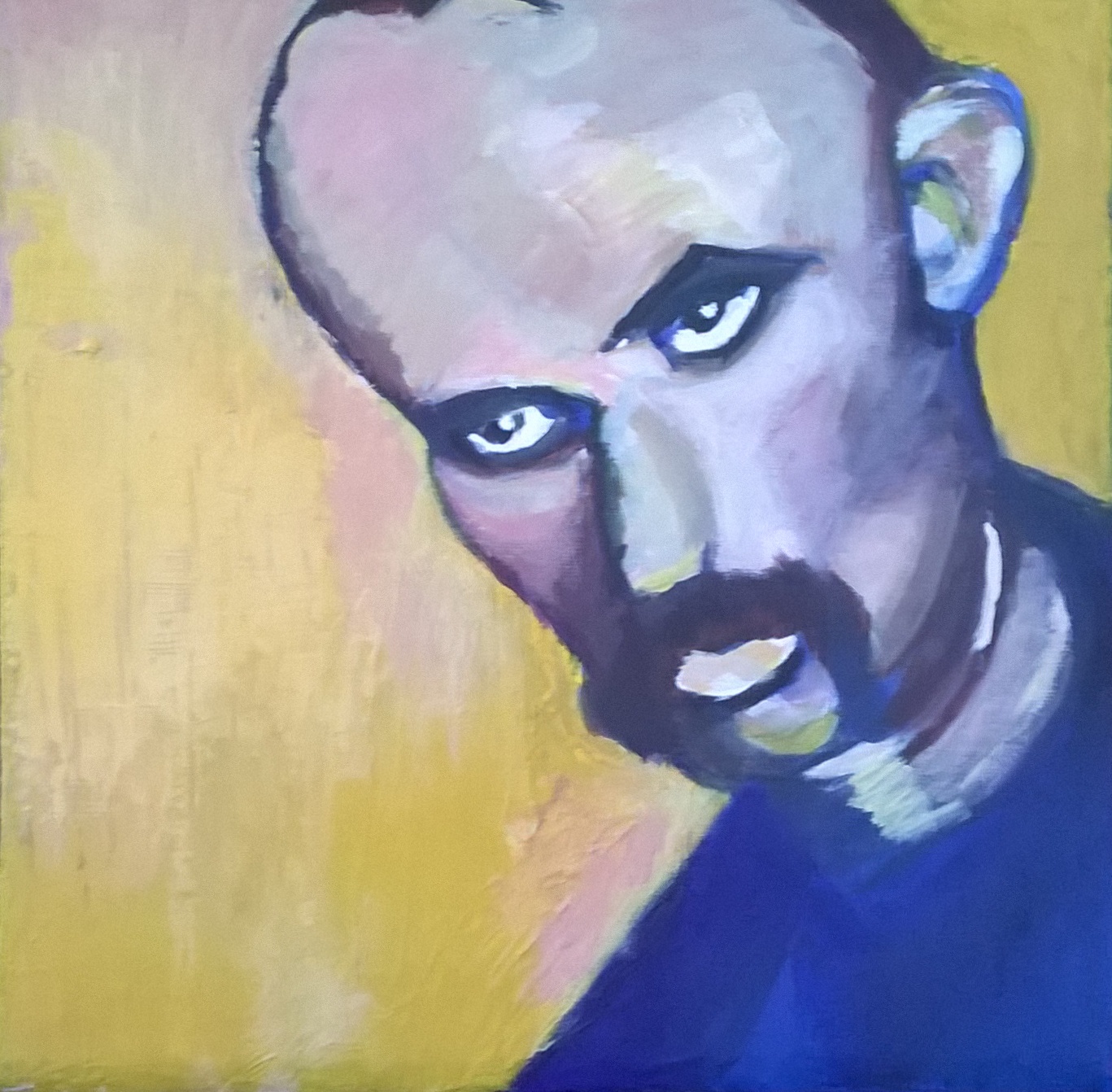

English Brother and Sister 12x12 |

|

|

|

Boy (sold) 12x12 |

|

|

| |